Basking in the Light of the “City of Paradise”

Image by Angela Acosta

At my library study carrel, I conjured scenes of children playing on rocky Andalusian shores and fishermen arranging their bountiful Mediterranean harvests. Vicente Aleixandre’s poem “Ciudad del paraíso”, translated as “City of Paradise” in English, transported me to Málaga, Spain where time stands as still as the mountains overlooking the sea below.

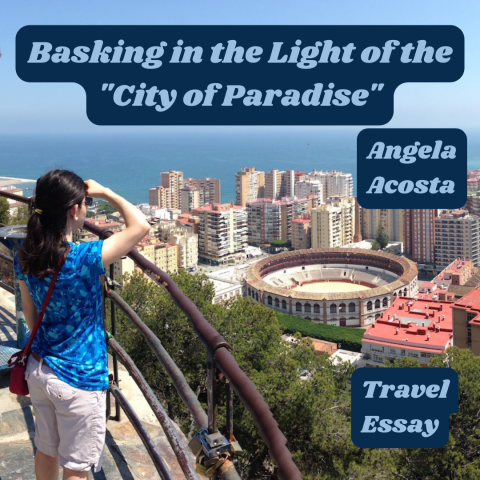

During my first visit to Málaga in May of 2016, I basked in the warm sunlight standing high atop the Gibralfaro fortress. Generations of locals called malagueños, from the Phonecians of Malaka to the Muslims of al-Andalus who built the fort over the Phonecian lighthouse, have stood for centuries in this very spot to keep watch over the multicultural community below.

Over time, these predecessors laid the bricks from which Málaga was built. Across these different Málagas, locals and tourists alike continue to admire its indomitable spirit. I ascend steps built a millennium ago, pass by Roman and Moorish city walls, and dine in restaurants whose Indian and Mexican fare can only be attributed to an influx of tourists and ex-pats.

Málaga was not always a happy oasis filled with museums, Andalusian architecture, and ice cream shops. During Aleixandre’s seaside childhood days in the early 1900s, textile factories populated the area by the port as malagueños labored tirelessly to keep the light of the city and its lighthouse, La Farola de Málaga, burning from the depths of economic hardships.

After Aleixandre moved to Madrid with his family in 1909, the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) broke out. Thousands of malagueños fled the city to nearby Almería as Francisco Franco’s troops stormed and bombed Málaga. The few who made it safely would forever remember La Desbandada, the massacre that took thousands of lives and almost destroyed Málaga for good.

Although physically unscathed, Aleixandre retreated into the depths of his nostalgic childhood paradise in his 1944 poetry collection Sombra del paraíso (Shadow of Paradise). “City of Paradise” delights the senses through vivid imagery of sunny southern Spain while also conveying the dull ache he felt for a city to which he could never fully return.

In a fitting tribute, he dedicates his poem “To my city of Málaga”. I already admired Aleixandre’s literary legacy in my research and translation work, but would I too become enamoured with the splendor of Málaga? In short, it was inevitable.

I sojourned to Málaga for practical, research reasons as well as a fervent desire to spend time somewhere that meant so much to Aleixandre that he continued writing about the city decades later. His poetic memories of Málaga would even help propel him to win the 1977 Nobel Prize in Literature.

It is one thing to admire Málaga for its tropical scenery of palm trees, beaches, and noisy quaker parrots and another to become fully immersed in retracing the steps of Aleixandre and his contemporaries: Pablo Picasso and Emilio Prados.

During my archival research trips to Spain, I spent the mornings taking copious notes at the library located at the Generation of 1927 Cultural Center. Friendly archivists guided me to sources about Sombra del paraíso and the many tributes to the friendships cut from the fabric of the cultural effervescence of Spanish modernism during the 1920s and 1930s.

Mementos of generations of writers and artists appeared around every corner. I nearly missed spotting a rather unassuming building on a narrow street near the port. It was there at number 6 on Córdoba street where Aleixandre lived with his parents and sister Conchita within view of the warm Mediterranean waves and sand.

An official plaque declares the house the residence of its “adoptive son”, Vicente Aleixandre. The city still shines today with tan tiles in the city center reflecting the glow of the summer sun as tourists and residents alike eagerly peer into escaparates, shop window displays, as the faint sea breeze and colorful abanico fans gently cool passersby.

After I satisfied my research appetite at the archive, I traversed paths Aleixandre himself took around the city. My next stop was the site of the Roman amphitheater where stray cats laze about under shady trees.

From there, I started a hike that took me to the Castillo de Gibralfaro (Gibralfaro Castle), a fortress overlooking the port. High atop the fort, I contemplated the “City of Paradise”’ with its hills that fall into the blue waves. It wasn’t until I inhabited Aleixandre’s paradise firsthand that I was fully prepared to translate and analyze poems from Sombra del paraíso.

The Málaga that I experienced in 2016 and again in 2019 now thrives as a tourist destination, but reminders of the past are literally built into the old city walls and archeological remains in the museum. Even though large container ships and cruise liners now dock at the port, visitors are greeted by the same bright sun and beautiful water of the Mediterranean.

The Gibralfaro Castle is one such timeless relic of Aleixandre’s youth and that of other bygone generations. The castle was constructed during the 14th century to house troops and protect the Arabic Alcazaba, currently protected by feline sentinels. I hiked for half an hour to reach the entrance to the castle on the hilltop and marveled at the impressive views of Málaga along the way.

I felt almost giddy as I smelled resplendent flowers and smiled at the families and couples also making their way skyward. Once I reached the top, I walked the walls of the castle to admire a 360-degree view of Málaga, now a bustling city of half a million people.

From the Castillo de Gibralfaro, I could see the Mediterranean Sea and imagine the people Aleixandre saw walking around selling fish in the old part of town. Although Aleixandre describes Málaga almost as a celestial place, his work is clearly telluric as he grounds himself in the city of his early childhood memories.

While Aleixandre begins his poem describing an ethereal city held up in the sky, cascading downwards towards the ocean, he later presents scenes of children laughing as they climb over rocks on the seashore and evokes images of elaborately decorated windows covered in flowers, an Andalusian delicacy.

Although the sea initially overtook my imagination, I remembered to look further inland while atop the Gibralfaro. Past the large Spanish flag proudly waving above me, I gazed in amazement at the rows and rows of buildings that spill inland to accommodate the growing population. Life in Málaga is flourishing and I yearned to experience as much of the city as I could.

Once I returned to lower elevation, I leisurely strolled down the path by the port marked with reminders of Jorge Guillén and other eminent literary figures. From there, I happily waded in the cool ocean water near a touristy sign for “Malagueta”, the beach closest to town.

For a moment the shouts of children and fluttering of the radiant green quaker parrots fell silent. I closed my eyes once more as I retraced Aleixandre’s verses in my head, returning to his century-old memories of a vibrant community nestled within the jewel of Spain’s sun coast.

Aleixandre’s homeland is not mine, but I have no doubt crossed paths made by my Spanish ancestors. What stories and mementos did they leave behind on the Iberian peninsula before braving the rough waters of the Atlantic to settle in Mexico?

My literary pilgrimage gifted me the ability to connect with cultures past and present to see the persistence of the literary and cultural legacies I study as part of my doctoral research.

From the tributes we make to Aleixandre and his friends of the Generation of 1927 to plaques and statues placed through Málaga, Sevilla, Madrid, and elsewhere in Spain, these homages sustain Aleixandre’s “City of Paradise”, illuminating it for generations yet to come.

Looking for more travel inspiration? Check out these posts from the MockingOwl Roost contributors and staff.

Angela Acosta

Angela Acosta is a bilingual Latina poet and scholar from Florida. She is currently completing a PhD in Iberian Studies at The Ohio State University. She won the 2015 Rhina P. Espaillat Award from West Chester University, and her work has or will appear in Flying Island Journal, Pluma, The Blue Moth, WinC Magazine, and MacroMicroCosm. When not teaching, she can be found conducting research on women writers in Spanish archives and enjoying churros with hot chocolate.

You may follow Angela on Instagram or check out her academic website.

2 Comments

[…] Basking in the Light of the “City of Paradise” – Literary Travel […]

[…] Basking in the Light of the “City of Paradise” […]